Having made the rank of master sergeant in the Army, I wish I could say I’ve also become a master in the art of photography. Far from it. When I look at the work published by National Geographic, Getty, AP or Reuters, I’ve barely reached the rank of specialist in comparison.

But even in my own journey, I love mentoring others. I get a kick out of sharing some tip with a young photographer, when he suddenly lifts his chin, dead-stares into my face and says, “Why hasn’t anyone told me this before?”

Nothing I do in my photography is a secret. I simply hope to share tips and ideas that have helped others (and myself) grow in this craft.

But before we go any further, I need to emphasize something: It’s the small stuff that become big. Let’s not pretend that this list will blow anyone’s mind. But I hope it will help you refine your process. I photographed and wrote a story on an orthopedic surgeon once who was also a President’s Hundred rifleman. He obsessed over the process of things: from grilling the perfect steak to doing surgery on a complete hip replacement (the two were unrelated, thankfully). In training for his rifle matches, he would spend hours in his basement aiming the barrel into a corner of the room, conducting dry-fire drills, over, and over and over again. For every trigger he squeezed in competition, he must have squeezed a thousand more in practice. Like rifle marksmanship, this craft requires work. There are no shortcuts, no secrets, no “god codes” to beat the game. Either put in the effort, or don’t be surprised when your work doesn’t improve.

Embrace the suck

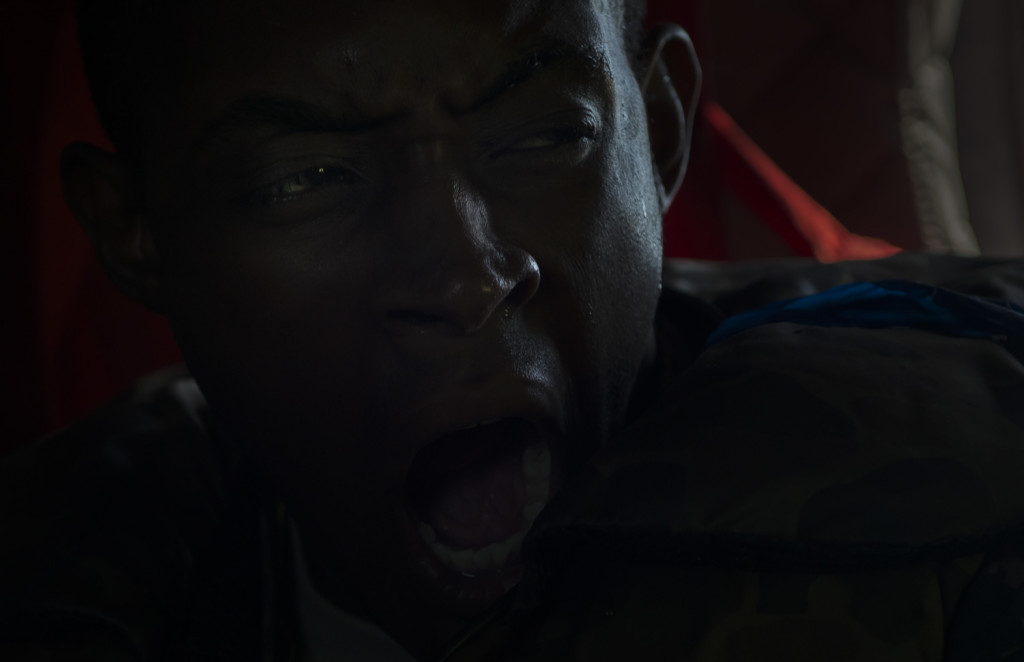

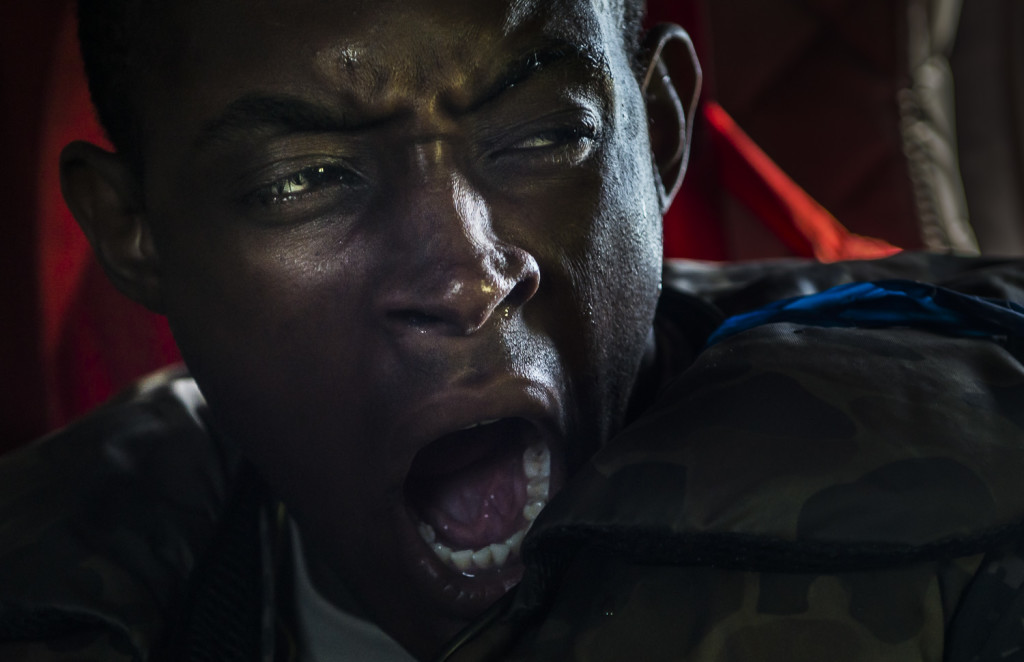

Pfc. Chauncey Harrison, a U.S. Army Reserve military police Soldier from Clarksville, Tennessee, receives a 5-second pulse shot by an X26 Taser during a taser familiarization training event conducted by the 290th MP Brigade and the 304th MP Battalion, both headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee, June 21, during Guardian Justice at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin. Guardian Justice is a military police specific training exercise that focuses on combat support and detainee operations skills. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

Before I tell you what you should do with your hands, your eyes or your camera, I want to help you understand something.

You will suck. A lot. And then you will suck some more. Then you will take one great picture. It will give you joy and hope and satisfaction. It will motivate you. Then you will suck even longer. You will continue sucking as you work. Then you will suck a little less. Then, eventually, you will look back at that one great picture you took and think, “Wow, that image kinda sucked.” Then, eventually, your work will improve.

I’m with you in that pain. It’s incredibly frustrating having that beautiful image unfold right in front of your eyes, taking the shot, only to realize you missed the moment. For whatever reason, the shot didn’t come out the way it was meant to be. Either you fired too late, or your settings were jacked up, or you abandoned the image too soon. For every image in my portfolio, there are probably 50 or more others I should have had that were better than the one I got. As you grow and become more intentional, your odds will improve.

There’s a video out there, five-and-a-half minutes long, of a skateboarder trying to land a trick off a set of steps in a parking lot. For five straight minutes, the video shows clips of him failing the landing, over and over again. At one point he smacks his head off the pavement. But he doesn’t stop. He perseveres. Finally, at the 5:10 mark, he lands the jump. Those first five minutes of video are edited down from likely hours-worth of attempts. It was the stereotypical “if you fall, you must get up” lesson on life, but it was so tangible and true.

Double barrel shooting

I was working with a Sapper company in San Luis Obispo, and a fellow photographer was invited to shoot the same mission. As you can see, I almost always have two cameras strapped to my side when I work. (Photo by Luigino De Grandis)

Stop going out with only one camera. When I cover Army assignments in the field or in fast-paced environments, I shoot with two cameras. I strap a wide angle lens on one body (usually a 24mm prime, but sometimes a 24-70mm, or even a 16-28mm), and a telephoto on the other (70-200mm, sometimes with a 2x converter). Too often photographers go out with a lens that can “do it all” (such as a 24-105mm), only to come back from a shoot with hundreds of images that all look the same. Having two bodies with two very different lenses will help you see images that you never considered before. It will also help you capture shots you were missing before.

The one exception I would make is if you are documenting something more personal or sensitive in nature, where barging in with two cameras would totally destroy the mood of the story.

Also, for you senior public affairs NCOs and Officers reading this: Quit sending Soldiers out with only one camera. You’re setting them up for failure. Fight the budget battle and buy your Soldiers the equipment they need. Otherwise, be content with sucky pictures.

Shoot stories, not pictures

U.S. Army Reserve combat engineer Soldiers from the 374th Engineer Company (Sapper), headquartered in Concord, Calif., took part in a two-week field exercise known as a Sapper Leader Course Prerequisite Training in July at Camp San Luis Obispo Military Installation, Calif. The unit is grading its Soldiers on various events to determine which ones will earn a spot on a “merit list” to attend the Sapper Leader Course at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

A group of U.S. Army Reserve Soldiers ride on the back of a troop-carrier truck after eating breakfast to go training on Fort Hunter-Liggett, California, May 3. Approximately 80 units from across the U.S. Army Reserve, Army National Guard and active Army are participating in the 84th Training Command’s second Warrior Exercise this year, WAREX 91-16-02, hosted by the 91st Training Division at Fort Hunter-Liggett, California. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

U.S. Army Reserve Soldiers from the 160th Military Police Battalion, of Tallahassee, Florida, conduct detainee enrollment training at Fort Hunter-Liggett, California, May 3, during a joint training exercise. Approximately 80 units from across the U.S. Army Reserve, Army National Guard and active Army are participating in the 84th Training Command’s second Warrior Exercise this year, WAREX 91-16-02, hosted by the 91st Training Division at Fort Hunter-Liggett, California. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

Capt. Osvaldo Tanon, U.S. Army Reserve chaplain with the 92nd Chaplain Detachment, of Mesa, Arizona, shaves using the mirror from a High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle while training in the field with military police Soldiers at Fort Hunter-Liggett, California, May 4. Approximately 80 units from across the U.S. Army Reserve, Army National Guard and active Army are participating in the 84th Training Command’s second Warrior Exercise this year, WAREX 91-16-02, hosted by the 91st Training Division at Fort Hunter-Liggett, California. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

Stories carry a narrative. They carry depth. When on assignment, think of the greater narrative unfolding around you. Don’t cover just the action, but the before and after, too. The quieter moments can hold a lot of emotion. Sometimes a single photo can punch with its own entire story, but don’t shoot and publish 15 images that all convey the same part of the story. Think of every photo assignment like a writing assignment. If each image were a paragraph in that story, would they all tell the same thing? Get in close and capture that intimate, difficult or powerful detail. Then back away and give us a sense of place and scene. It’s entirely too easy to shoot images cropping people at the belly button or chest. Get closer. Give me eyes and teeth. Document both action and reaction. Photograph images that reveal character and people’s personalities, not just what they do as their job.

Feed your camera raw meat

Always shoot in RAW format. This image is clearly way under-exposed. I had my exposure settings for outside of the helicopter, when suddenly I saw this Soldier yawn. I turned around and I grabbed him, but the image was completely black. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

With a bit of post-production work, I was able to recover the image. Yes, you should always strive to get it right in camera, but sometimes it’s nice to have that RAW file save you! (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

Stop shooting in JPEG. Whether Canon, Nikon, Sony or other, your camera (most likely) can shoot in a RAW format. Always shoot in RAW. Always. RAW files allow you more control when color correcting, adjusting exposure or even salvaging images that were blown out or under exposed. Whenever you edit from a RAW file, you will produce a much “richer” image in return.

Yes, RAW files take up more space. A ton more space. Invest in memory cards and hard drives. You should go out with a minimum of two 32GB memory cards on every assignment. That doesn’t mean you have to fill them! But have that memory space available.

Framing is caring

Sometimes you can’t get close enough to the shot in time to grab it the way you want it. Shoot for that moment, and know that you can crop it later. (U.S. Army Reserve photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

Here is the cropped version. It’s perfectly fine to crop in tight. With most cameras, you have plenty of pixels to spare: U.S. Army Soldiers go through a decontamination tent during Guardian Response 17 at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center, Indiana, April 26, 2017. Guardian Response is a multi-component training exercise run by the U.S. Army Reserve designed to validate nearly 6,000 service members in Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) in the event of a Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) catastrophe. This year’s exercise simulated an improvised nuclear device explosion with a source region electromagnetic pulse (SREMP) out to more than 4 miles. The 84th Training Command is the hosting organization for this exercise, with the training operations run by the 78th Training Division, headquartered in Fort Dix, New Jersey. (U.S. Army Reserve photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

We have all heard the rule of thirds in framing, but more importantly, I follow a three-step rule to framing my shots: Fill the frame. Control the background. Capture the moment.

Fill the frame: To be honest, when I shoot images, I typically frame the shots about 15 to 20 percent wider than they need to be. Later, when I edit on the computer, I crop that sucker down to include only what’s essential. Play with cropping a lot! Sometimes playing with a single image for five minutes on cropping can open up options you never considered. Cropping down an image (even cropping drastically) can have a huge impact.

Control the background: Sometimes moving a foot to the left or right, or crouching down a little, can significantly improve the shot. Be intentional. Think about each frame. Look not only at what’s in front of you, but what’s behind the subject. Some of it you can remove with cropping, but a lot you can’t.

Capture the moment: Now that you’re in place, that’s when you want to burst through that moment. I’ve seen so many photographers (myself included) abandon a shot too early. They’ll shoot two or three frames and then move on to something else. Sometimes that spot you picked could have been perfect if only you had shot four or five more frames! Wait for that perfect moment to come, and burst through it (or time it perfectly if you can!).

Anticipate and be patient

You have to anticipate and visualize the shot before it happens. And sometimes you get lucky, like I did here with a Soldier pointing and framing the dummy in the background perfectly. But you have to be in the right place and at the right time and be patient, otherwise luck doesn’t count for much: A mannequin lies in the rubble of a training site during Guardian Response 17 at the Muscatatuck Urban Training Center, Indiana, April 27, 2017. Guardian Response, as part of Vibrant Response, is a multi-component training exercise run by the U.S. Army Reserve designed to validate nearly 4,000 service members in Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) in the event of a Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) catastrophe. This year’s exercise simulated an improvised nuclear device explosion with a source region electromagnetic pulse (SREMP) out to more than 4 miles. The 84th Training Command is the hosting organization for this exercise, with the training operations run by the 78th Training Division, headquartered in Fort Dix, New Jersey. (U.S. Army Reserve photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

For many years, I had photography Attention Deficit Disorder (sometimes I still do). I would jump around nonstop trying to chase everything, afraid I might miss something.

Stop.

An Army Reserve combat engineer from the 364th Engineer Company (Sapper), out of Dodge City, Kan., jumps out of a CH-47 Chinook helicopter flown by Bravo Company, 7th Battalion, 158th Aviation Regiment, out of Fort Hood, Texas, during Operation River Assault 2015. The bridging training exercise involved Army Engineers and other support elements to create a modular floating bridge on the water across the Arkansas River at Fort Chaffee, Ark., Aug. 4, using improved ribbon bridge bays. The entire training exercise lasted from July 25 to Aug. 7, involving one brigade headquarters, two battalions and 17 other units, to include bridging, sapper, mobility, construction and aviation companies. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

There are times when you can anticipate the action before it fully unfolds. Make a decision. Pick the best spot. And wait. Then, when the moment is right, shoot that image. Sometimes you will have to move because there’s a better spot somewhere else, but once you make your decision, stay in place. Doing this will feel wrong at times. It will feel like you’re missing everything else. That may be true. You might miss an even better shot elsewhere, but you have to learn to make decisions on what’s important to document and what’s not important. If you chase every flying object, you will not grow in your decision making. Yes, there will be times when you have to chase and run after a shot, but there will times when the best thing you can do is pick one spot, sit and anticipate.

Earn their trust

A U.S. Army Reserve military police Soldier from the 341st MP Company, of Mountain View, California, fires an M249 Squad Automatic Weapon mounted on a High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle turret during a night fire qualification table at Fort Hunter-Liggett, California, May 4. The 341st MP Co. is one of the first units in the Army Reserve conducting a complete 6-table crew-serve weapon qualification, which includes firing the M2, M249 and M240B machine guns both during the day and night. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

A U.S. Army Reserve combat engineer Soldier from the 374th Engineer Company (Sapper), headquartered in Concord, Calif., checks his watch before a night land navigation course through the hills of Camp San Luis Obispo Military Installation, Calif., July 15, during a two-week field exercise known as a Sapper Leader Course Prerequisite Training. The land navigation course began after dark and most Soldiers didn’t finish until after midnight after trekking for miles through the steep hills. The unit is grading its Soldiers on each event to determine which top ones will earn a spot on a “merit list” to attend the Sapper Leader Course at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. (U.S. Army photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

Nobody likes a public affairs Soldier who shows up dead-smack in the middle of a training event, takes a bunch of pictures, asks questions (disrupting everyone), then disappears. You need to show up early. You need to be there when Soldiers are planning and preparing. This is good for several reasons: You will get better information. You may capture images you didn’t consider. You will earn the trust of those Soldiers. That trust will result in better, deeper stories. Yes, there will be a point when you have to take off to edit your work, but it’s not unreasonable to put in 14-hour days (or longer) when covering stories. Get the work done.

Submit for awards

Awards are nice, but notice I didn’t say, “Win awards.” I said, “Submit.” You don’t get better by winning awards. But you do get better by submitting. Why? It’s not just because it drives your competitive spirit or fuels your desires or passions. It’s more important than that. By submitting, you will be forced to look back. You will have to look back at 12 months of sucky photos and assess your strengths and weaknesses. It will help you realize where you need to improve. Also, because most awards competitions have categories, it will help you think of ideas or themes that you might not have considered before. Always look at past years’ winners. Study them. Learn from their talent. But most importantly, if the judging is “open” or has a live stream, watch it, listen carefully to the judges’ comments and take notes!

Embrace the criticism

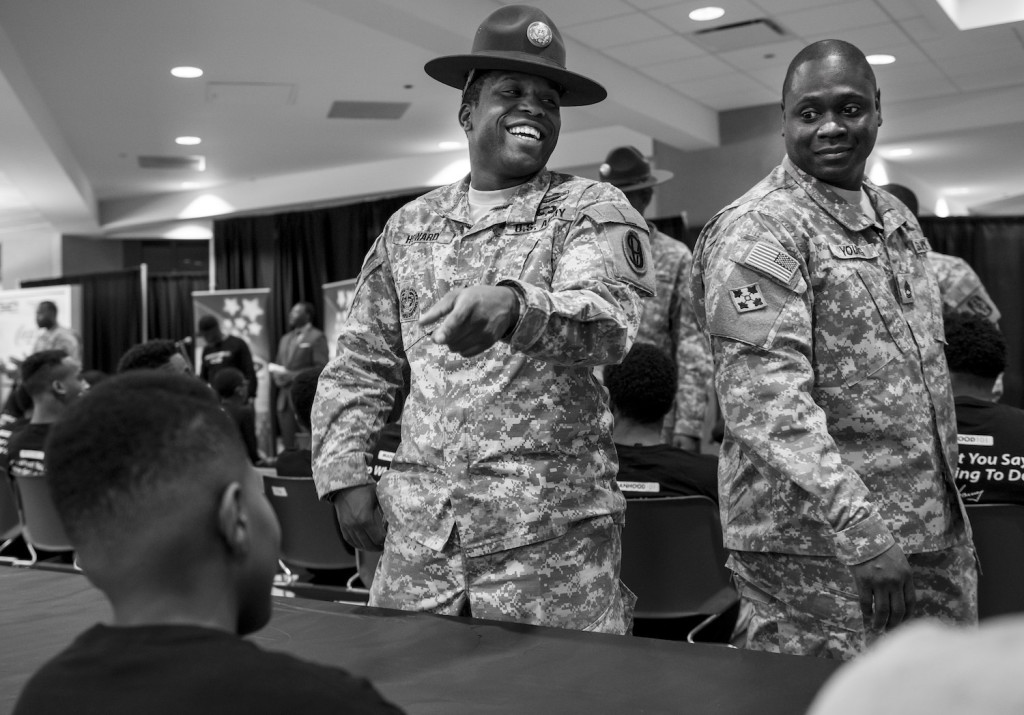

Staff Sgt. Dennis Howard, an Army Reserve drill instructor with the 2-330th Infantry Battalion, One Station Unit Training, and Sgt. 1st Class Michael S. Young Jr., an assistant inspector general for the 416th Theater Engineer Command, joke with a Chicago teenager during the Steve Harvey Mentoring Weekend hosted at Chicago State University the weekend of Jan. 23-25. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. 1st Class Michel Sauret)

Not all criticism is created equal. Some is more helpful than others. But whatever you do, don’t try to defend your work against the criticism of others. Embrace it. Take it all in. Be humble. Maybe they’re right. Maybe you really do suck. True, sometimes you will hear from three different people, each saying something completely different and contradictory. I’m not saying to please your critics. You can’t, and you never will. But make the effort to learn from their critiques. Take time to truly digest what they’re saying. Try out some of their recommendations. If those ideas work, put them in your toolbox. If they don’t work, keep exploring and keep seeking feedback. Join online groups, but stay away from toxic “communities.” Seek out communities that really want to invest in improving others.

Find a mentor

Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Moeller, U.S. Army Reserve drill instructor and the 2016 U.S. Army Noncommissioned Officer of the Year, participates in a marketing photo shoot organized by the Office of the Chief of Army Reserve at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, Feb. 14, to promote the U.S. Army Reserve. (U.S. Army Reserve photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret)

This is probably the most important thing you can do, but I leave here at the end because if that’s all you remember then you’re good shape. Also, mentorship is true in every area of life, not just photography. Just like seeking criticism, also seek out one photographer whose work you respect and admire and who is willing to spend time with you to review your portfolio, give you encouragement and help you grow.

If you’re a military photographer, free to reach out to me. I’m always happy to give you an honest review of your work, photo website or portfolio.

Then, I hope to hear back from you in 12 months, when, hopefully, your work (and my work) will suck a little less.

Michel Sauret – Award-Winning Army Journalist | Independent Author Award-Winning Army Journalist, Independent Author

Michel Sauret – Award-Winning Army Journalist | Independent Author Award-Winning Army Journalist, Independent Author